While Windsorites ready the champagne and prepare to ring in the New Year, we are standing on the anniversary of a terror most locals have forgotten – or simply never knew.

Today is December 29th. In the 1850s, this wasn’t just a holiday break – that fuzzy, unknown time between Christmas and New Year’s, where we eat and drink too much while forgetting what day it actually is: it was the beginning of the Heartbreak Days for enslaved Black Americans.

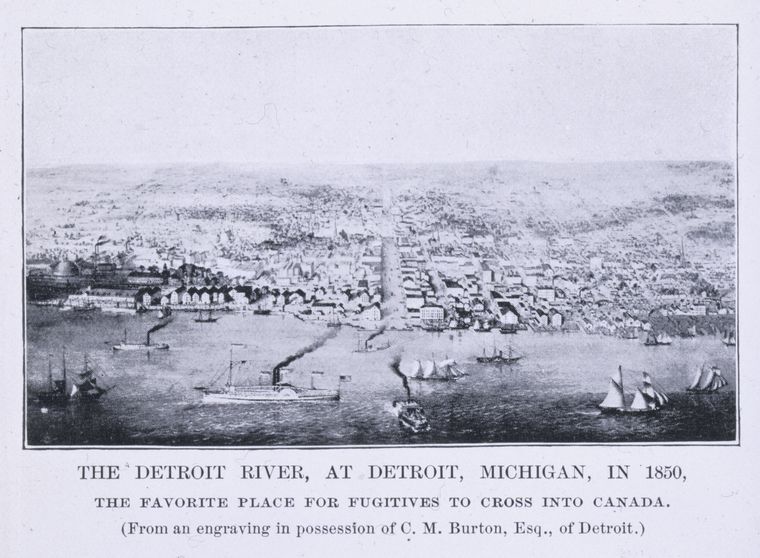

For thousands trapped in slavery, the Detroit River – known as the Terminus of the Underground Railroad – was the finish line of a desperate, heart-pounding race against a calendar designed to destroy them. Why? January 1st was “Hiring Day” – the end of the fiscal year, when contracts expired, debts were settled, and families were sold off like surplus inventory to the highest bidder.

We love to boast around here that we were the ‘destination’ for those freedom seeking slaves, but we’ve developed a convenient, selective amnesia about the actual cost of what that journey truly meant.

It’s easy to sell the sanitized ‘Freedom Narrative’ in history books, tourism brochures, and early education, where we learn about noble whites who themselves made great risks and sacrifices, offering lodging in safe houses along the route; it all makes it sound like a polite, organized migration.

But history is rarely polite, or neatly organized.

The real version is gritty, and it included the “Order of the Men of Oppression” – a secret abolitionist society modeled after the Masons, committed to liberation through secret routes utilizing secret phrases and wagons with false bottoms. This wasn’t just a humanitarian effort; it was an underground international journey.

Upon arriving by late December, the Detroit River was often a slushy mix of ice and water. If you swam, you’d risk dying. If you took a rowboat, you’d risk being spotted by bounty hunters looking for a $10 New Year’s bonuny; the perverse Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 incentivized the capture and return of escaped slaves to servitude with double the standard rate at New Year.

Run and maybe freeze. Stay and certainly shatter. Those were the choices.

Walk down Riverside Drive today and there are monuments and symbols commemorating industry, war, art, and more. But the site of the most significant human rights victory in the 19th century – the shoreline where the Terminus of the Underground Railroad ended in a gasp of frozen relief – is often relegated to a backdrop for selfies or festivals. And while the “Tower of Freedom” monument stands on our side of the river – and mirrored in Detroit – we Must do more than just build statues.

We must fund our Black historical sites to ensure this history – our collective history – is told year-round and not just during the shortest month of the year – Black History Month in February. Take The Sandwich First Baptist Church for example! It wasn’t just built for prayer; it was built with a literal trapdoor to hide hunted slaves. Its bells didn’t just call the faithful to service; they rang to warn that bounty hunters were prowling our streets seeking to retrieve escaped slaves living freely.

Windsor wasn’t just built on salt and cars: it was also built on the grit of people who reached these shores on New Year’s Eve, soaking wet, half-frozen, and finally – legally – free.

Between 1850 and 1860, Windsor’s Black population surged by over 100%. That isn’t just a statistic; it is a testament to the thousands who chose ice blocks rather than risk the auction block.

By ignoring the agony of the Heartbreak Days, we aren’t just forgetting our collective past – we’re insulting survivors by pretending freedom was a gift given, rather than something earned through absolute personal hardship.

As you count down to midnight this year, look across the river, and don’t just see the Detroit skyline. See the Terminus of the Underground Railroad, and remember that for some, the new year didn’t just mean resolutions – it also meant freedom.

Leave a Reply